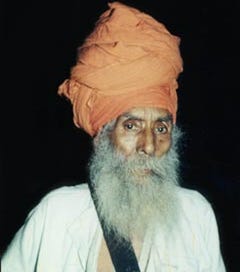

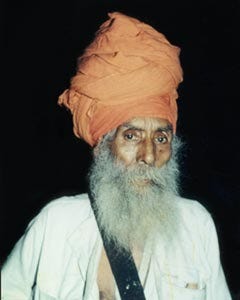

In a world where charity is often curated for cameras and filtered for applause, where social media turns selfless moments into personal brand-building, the life of Bhagat Puran Singh stands apart like a solitary lamp burning quietly in the wilderness. No attention, no retweets, no audience.

He walked through Amritsar’s heat and Lahore’s monsoon not with placards, but with patients. No film crew followed him. No microphones caught his voice. His only announcement was a brass bell tied to his side, gently ringing as he walked.

Born on June 4, 1904 in the village of Rajewal in Ludhiana district, his formal education ended early. But what his life lacked in institutional degrees, it overflowed with experiential wisdom. In Lahore, at the steps of gurdwaras steeped in martyrdom, his vision took form: If the forgotten had no one, they had him.

ਆਪੁ ਗਵਾਇ ਸੇਵਾ ਕਰੇ ਤਾ ਕਿਛੁ ਪਾਏ ਮਾਨੁ ॥ (Ang 474)

Only the one who dissolves the self in seva earns a place of honour.

This was a man who gave his life to seva long before the term was hashtagged. There was no content calendar. No brand collaboration. No headlines to ride. What Bhagat Puran Singh built with blistered feet and sleepless nights was not a charitable enterprise, but a lived challenge to every bystander who passed the dying on the roadside and looked away.

He named the institution Pingalwara — literally “home for the crippled.” The word itself was stark, unembellished, even awkward. It didn’t sell a dream. It revealed a wound. And yet, this space would become sanctuary to those too sick, too poor, too unclean for hospitals or homes.

ਸੇਵਾ ਸੁਰਤਿ ਸਬਦਿ ਵੀਚਾਰਿ ॥ (Ang 1343)

Seva flows from the Guru’s wisdom that stirs consciousness.

Bhagat Puran Singh wasn’t a fundraiser. He was the one lifting the soiled, dressing the rotting, and staying awake beside the abandoned. His hands held cracked palms, emptied bedpans, and lifted bodies stiffened by cold and indifference.

While others debated social policy or drafted white papers on public health, he was washing gangrenous limbs, cleaning ulcers, and cradling infants with deformities no one else would touch. Where charity was often reduced to a transaction, he made it a complete offering — of time, of dignity, of the body itself.

Bhagat Puran Singh’s seva was never pegged to the crisis of the day. He didn’t chase relevance. He did not serve in reaction to public emotion. His service had its own quiet momentum, unaffected by news cycles or national moods. He wasn’t waiting for a story to break so he could appear noble by association.

And this is where the contrast is most jarring. Today, good deeds are often measured not in impact but in impressions. Human suffering is edited into montages. Acts of compassion are recorded from flattering angles. But Bhagat Puran Singh kept walking barefoot, dragging a cart behind him, carrying a child riddled with disease. The world did not watch. And he never asked it to.

ਤੇਰੀ ਸੇਵਾ ਤੁਝ ਤੇ ਹੋਵੈ ਅਉਰੁ ਨ ਦੂਜਾ ਕਰਤਾ ॥ (Ang 1185)

True seva arises from within. No one else can walk that path for you.

He remained untouched by the seduction of recognition. He was not a symbol of virtue. He was its labourer. And perhaps that is why he saw maya — the shameless, shape-shifting force of illusion — for what it was.

ਨਕਟੀ ਕੋ ਠਨਗਨੁ ਬਾਡਾ ਡੂੰ ॥ ਕਿਨਹਿ ਬਿਬੇਕੀ ਕਾਟੀ ਤੂੰ ॥ (Ang 476)

The shameless noise of worldly illusion is loud. Only a discerning soul dares to silence it.

Bhagat Puran Singh did not need the validation of wealthy patrons. He had bibek — clear-sightedness — that allowed him to see through ceremonial charity, to the core of what mattered.

And in doing so, he is forcing a mirror upon the rest of us. Not through condemnation, but through contrast. While we outsource our empathy and express it through monthly deductions, he bled it out through his own skin.

Bhagat Puran Singh’s legacy and service cannot be templated.

He was Guru Nanak’s Sikh, where each step beside the suffering was a hymn, each touch of the forgotten a sacred offering, and seva, a silent song etched in flesh and spirit.

Bhagat Puran Singh passed in 1992 — before mobile phones, before filters, before styled generosity. But even if they had existed, he wouldn’t have noticed. His service wasn’t for the feed.

In remembering him on his birth anniversary, we are not simply recounting a story. We are being asked a question. Will we continue to consume charity as a spectacle? Or will we, too, one day, pick up a banana peel from the road and start walking — without a camera behind us? Guru Mehar!

(The author is a career journalist and currently serving as Communications and Advocacy Director at UNITED SIKHS (UK), a charity registered in England and Wales)